Who is That Pickleball Guy: Kyle Koszuta?

Kyle Koszuta still keeps the script. Twenty years after his fifth-grade performance as Harold Hill in The Music Man, the yellowed pages sit in his Phoenix bookshelf, every line highlighted in marker, a testament to the kind of obsessive preparation that would define his life. "I memorized all these lines," he says, flipping through the dog-eared playbook. "I can't remember being more prepared for anything in my life."

Kyle had never been the star of anything—always stage crew, never the lead. He never really cared enough to be.

But when his elementary school's new music teacher announced they'd be staging a full Broadway-style production, something shifted. Maybe it was Danielle, the girl playing the female lead. Maybe it was the chance to finally step into the spotlight. Whatever the reason, ten-year-old Kyle found himself auditioning for Harold Hill.

The audition was a disaster. His friend Evan went first and was brilliant—gesticulating, singing with confidence. Kyle followed and felt like he "absolutely sucked." He cried in the car afterward, certain he'd failed. But clearly it wasn't as bad as he thought, because he got the part two days later.

What happened next would establish a pattern that would follow Koszuta for the rest of his life: when something mattered to him, really mattered, he would prepare with an intensity that bordered on obsession. He studied those lines everywhere—on planes, at dinner, practicing with every house guest his parents entertained. His mother ran lines with him nightly. He worked harder at memorizing that script than he'd worked at anything in his ten years of life.

The payoff was intoxicating. When the curtains opened, every line landed perfectly. He didn't miss a single cue. He also experienced something he'd never felt before: the rush of commanding a stage, of holding an audience's attention, of being genuinely good at something that required both preparation and performance under pressure.

It was the first time Kyle Koszuta learned that obsessive preparation could transform you from background player to star.

Twenty years later, it's a revealing artifact from someone who has built a career teaching the mental side of sports. As "That Pickleball Guy," Koszuta has amassed 400,000 followers across social media platforms, created a thriving online education business, and achieved professional status in America's fastest-growing sport.

But his story isn't really about pickleball at all. It's about what happens when the thing you've prepared for your entire life—the thing you've sacrificed everything to achieve—falls apart not because of your body, but because of your mind.

The Golden Child

Growing up in Niceville, Florida, Koszuta seemed destined for athletic success. His father, a doctor who somehow never missed showing up to Kyle's game despite being up by 4:00AM and at the hospital by 5, instilled a work ethic that bordered on the pathological. His older brother provided a roadmap: whatever sport Brad played, Kyle followed. Soccer, basketball, tennis, even marching band—Kyle absorbed it all with the focused intensity he'd shown memorizing every line of that school play.

"Character is better caught than taught," Koszuta recalls learning from a mentor, and he caught plenty from his family.

The Camp That Changed Everything

But it was a basketball camp in tenth grade that would prove to be one of the most transformative experiences of his life—perhaps more influential than any coach or game he'd ever encountered. PGC Basketball marketed itself as a summer camp but was really, as Koszuta puts it, "basketball camp disguised as leadership training."

The camp's founder, Mano Watsa, had created something unlike anything Koszuta had experienced. Watsa had built "a culture of service, of high energy, of great people doing the right thing over and over again.”

The curriculum went far beyond basketball fundamentals. Campers learned life principles that would stick with Koszuta for decades: if you're at the grocery store, don't just put your shopping cart in the parking lot—walk it back and grab another one on your way. Use people's names when you meet them. Look people in the eyes when you say thank you.

More crucially for his future, the camp taught a level of strategic thinking that revolutionized how Koszuta understood competition. Dead ball time, for instance, wasn't just a pause in play—it was an opportunity to huddle with teammates, assess the score and shot clock, and plan the next possession.

The camp taught players how to interact with referees—learn their names, be friendly, because "at the end of a game they might give you a call." It was an early introduction to what Koszuta now calls "the nuance of winning": the small psychological advantages that separate good players from great ones.

But perhaps most importantly, the camp addressed the mental side of the game in ways that traditional basketball coaching never did. While most programs focused on physical skills and basic strategy, PGC taught players how to think clearly under pressure, how to maintain confidence through adversity, and how to process information quickly without overthinking.

"That information is so deeply embedded in my brain," Koszuta says, "that transferring to pickleball, I feel like I'm just teaching basketball again."

Koszuta was so impacted by the experience that he returned as a counselor for five years, eventually leading camps himself. The analytical framework and leadership principles he absorbed became foundational to his worldview. Years later, when his basketball career crumbled and he needed to rebuild his relationship with competition, it would be these lessons—not the specific basketball skills—that proved most valuable.

The Collegiate Dream

The irony wouldn't become clear until much later: the camp that had given him the mental tools to succeed at basketball would ultimately provide the foundation for his success in an entirely different sport.

By high school, he was all-state in basketball, player of the year in his region, and completely convinced that Division I stardom awaited. He studied game film like a doctoral candidate, analyzed players like JJ Redick and Steve Nash, and trained religiously.

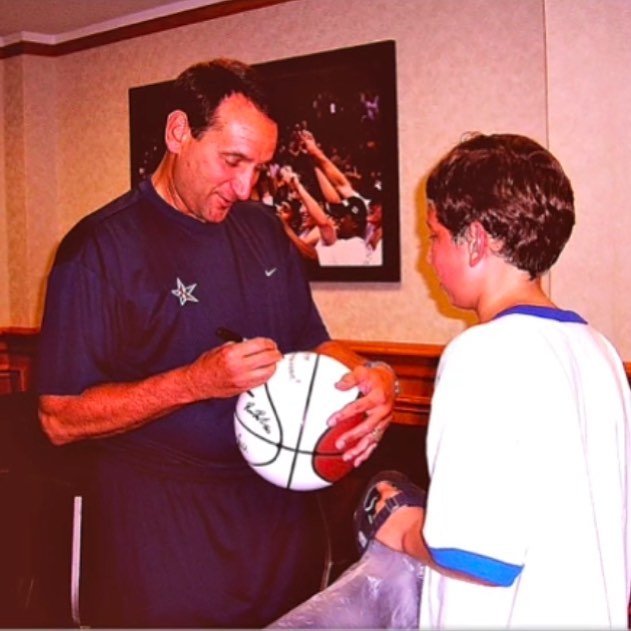

The dream felt tantalizingly close during his AAU career, when he found himself on court with future NBA players like Julius Randle. In one crystalline moment that he jokingly shared, Koszuta had a clean look from beyond the arc with ten seconds left, his team down three. Coach K sat courtside along every big name college basketball coach you could think of. "I look over at Coach K, and I'm like, this one's for you, Coach," Koszuta remembers. "And then the ball flies through the air…and doesn’t even touch the rim...a complete airball….and we lose the game."

Duke never called. In fact, only one Division I program did: the University of Louisiana at Monroe, a school Koszuta diplomatically describes as being in "Duck Dynasty territory." With a two-week deadline on the offer, he took it.

The Unraveling

College basketball, Koszuta quickly learned, was a different beast entirely.

At Louisiana Monroe, he discovered what every former high school star eventually learns: everyone here used to be the best player on their team. Suddenly, the kid who had dominated through basketball IQ found himself as "the least athletic guy on the court," struggling to keep up with players who could do everything he could do, only faster and higher.

But Koszuta adapted. He'd always been cerebral, so he became more cerebral. "I had to know where they were going before they went there," he explains. It worked—freshman year, he carved out a role as a contributor, playing 15 minutes per game and earning respect for his court awareness.

Sophomore year started even better. The team played Kansas at Allen Fieldhouse, where Koszuta found himself on the same court as Andrew Wiggins and Joel Embiid. He was named the team's sixth man, a key contributor on a squad looking to improve on their four-win season.

Then, for reasons he still can't fully explain, everything fell apart.

"I just stopped playing well," Koszuta says, the pain still audible in his voice. "I was losing confidence in myself, couldn't make shots. And became less valuable to the team."

What followed was a slow-motion collapse that anyone who has played competitive sports will recognize with a shudder. Sixth man became seventh man. Seventh man became benchwarmer.

By season's end, the coach had essentially stopped coaching him altogether.

The real damage was psychological, a kind of athletic depression that seeped into his everyday life. "I would just go in my room and scroll Instagram or something and just be sad a lot," he recalls. "Every day felt like life or death even though I knew it wasn’t. I was living and dying with how well I performed, completely consumed by whether I’d make shots or play well the next day."

The Mental Injury

During our conversation, I suggest that his mental struggles might parallel a physical injury—something that starts small but deteriorates over time, creating scar tissue that never fully heals. Koszuta pauses, struck by the analogy.

"I've never made that connection like that," he says. "That's such a good comparison... Yes."

He describes how, even after transferring to Rollins College in Orlando for a fresh start, the self-doubt followed him like a chronic condition.

"When I was in my junior and senior year, a lot of times when something would happen, I could definitely feel it being like, 'here we go again. Oh man, I'm not good. This is just like ULM…I suck…"

This is the cruel irony of Kyle's story.

His greatest strength—his analytical mind, his ability to break down complex situations and find strategic solutions—became his greatest weakness. While "less analytical" players might bounce back from adversity through sheer obliviousness, Koszuta's intelligence trapped him in cycles of self-analysis and doubt.

The mental injury proved more debilitating than any physical ailment he'd experienced. He could study more film, practice longer hours, analyze every mistake in excruciating detail—but none of it could repair the fundamental break in his confidence. "I don't think I ever fully recovered to the player that I once was," he admits.

By senior year at Rollins, he was still falling into ruts, still unable to access the freedom and joy that had once made basketball feel like art rather than arithmetic. When his career finally ended, his dominant emotion wasn't sadness but relief.

"I was just happy," he says. "I'm like, I'm so over the emotions, the up and down emotions, the feeling like you're better than you're playing."

The Exile

What followed was a complete exile from the sport that had defined his identity for nearly two decades. Koszuta didn't play basketball for two and a half years. He didn't even watch it for two or three years.

"You can work as hard as humanly possible," he reflects on those lost years. "And that is just the price of admission to get in the door. It doesn't guarantee anything."

Instead, he threw himself into a different kind of education. At the Florida Hospital Innovation Lab (FHIL), he learned design thinking and creative problem-solving, facilitating groups of healthcare workers through complex challenges. It was collaborative, creative work that felt like the opposite of the isolated mental prison basketball had become. The facilitation skills he'd first glimpsed at PGC Basketball camp now found new purpose in helping medical teams solve complex problems.

He also discovered improv comedy, spending years training in the "yes, and" philosophy that would later prove crucial to his content creation. It follows a foundational rule: accept whatever reality your scene partner establishes ("yes") and then build upon it with something new ("and").

If someone hands you an imaginary feather, you don't reject it by saying "that's a glass of water"—you accept the feather exists and add to the scene. The philosophy proved essential to his content creation approach: instead of waiting for perfect conditions or lamenting his beginner status, he accepted his reality as a pickleball newcomer and built compelling content around that journey.

The First Game of Pickleball

On August 26, 2021—Koszuta remembers the exact date—he played pickleball for the first time. It was supposed to be a casual date activity at a Scottsdale park. Instead, it triggered something that had been dormant for years: the pure joy of athletic competition.

"I went back the next morning around 7 a.m. to the same park, just by myself, played again," he remembers. Within months, he was playing five days a week and setting an ambitious goal: become a professional pickleball player within 12 months.

But this time would be different. This time, he had a plan that went beyond just playing.

Drawing on his marketing background and content creation skills developed during COVID, Koszuta launched "That Pickleball Guy" as both a personal brand and a public accountability mechanism. He would document his journey from complete beginner to professional, creating educational content that combined his analytical strengths with hard-won wisdom about the mental side of sports.

The strategy worked. His Instagram account grew from zero to 100,000 followers. His newsletter built a devoted readership. He landed a Selkirk sponsorship. Within 18 months, he was not only competing at the professional level but had built a business around pickleball education.

More importantly, he had found a way to transform his greatest weakness—that overthinking, analytical mind that had torpedoed his basketball career—into his greatest strength.

The same obsessive attention to detail that had trapped him in cycles of self-doubt now fueled detailed breakdowns of strategy and technique that helped thousands of players improve their games. Those lessons from PGC Basketball camp about maximizing dead ball time and thinking systematically about competition? They became the backbone of his educational content, translated from basketball courts to pickleball courts with devastating effectiveness.

The Wound That Heals

Today, Kyle runs ThatPickleballSchool.com with his longtime friend Tyler, the same person who had witnessed his basketball struggles years earlier. Their online community attracts what Koszuta calls "obsessed people"—players who don't just want to hit the ball around but want to understand every strategic nuance of the game.

He can now spend hours breaking down game film, organizing thousands of video clips into hundreds of strategic categories, and discussing the minutiae of shot selection with a community just like him.

"There was a time me and Joe [a training partner] got on the phone," he laughs, "and we had this spirited debate for 30 minutes" about whether to hit more third-shot drops or drives. So engrossed in the conversation, he drove 30 minutes in the wrong direction without realizing it. When he discovered he is now 45 minutes from his house, he drove in the right direction and called Joe back for another 45-minute strategy session.

It's the kind of obsessive behavior that might have seemed pathological during his basketball struggles. In the context of creating pickleball content, it's exactly what his audience craves.

But the mental struggles haven't disappeared entirely. Koszuta still experiences the same cycles of doubt and confidence that plague all competitive athletes. Just weeks before our interview, he had played poorly at the US Open and felt, for the first time in years, like quitting. The very next tournament, he earned his first professional medal with a second-place finish in men's doubles.

"This doesn't make any sense," he marveled. I actually really, I genuinely wanted to quit last week. And now I'm on championship Sunday."

But now he has the tools to recognize these patterns, to understand them as part of the process rather than evidence of fundamental inadequacy. More importantly, he has a platform to help others navigate the same mental challenges that nearly ended his athletic career.

The Lesson

Koszuta's story offers something rarer than inspiration: insight into how athletic trauma can be transformed into athletic wisdom. His basketball career didn't fail because he lacked talent or work ethic—it failed because the mental side of sports is often the most neglected and least understood aspect of competition.

In building his educational pickleball empire, Koszuta has created something that didn't exist during his basketball years: a framework for understanding and overcoming the psychological barriers that derail so many athletic careers.

"I really know the emotions of sucking in basketball," he says with characteristic directness. "I have been the best player and I have been the worst player."

That knowledge, painful as it was to acquire, has become his greatest asset. In a sport growing at breakneck speed, filled with newcomers struggling to understand not just how to play but how to think about playing, Koszuta offers something invaluable: the perspective of someone who has been broken by sports and learned how to rebuild.

The yellowed script from The Music Man still sits on his bookshelf, a reminder of a time when preparation and talent felt like enough to guarantee success. Now he knows better. But in that hard-won wisdom lies the foundation for something more sustainable than any individual athletic achievement: the ability to help others avoid the mental traps that nearly cost him everything.

In pickleball, Koszuta found more than a second chance at athletic success. He found a way to transform his greatest failure into his most valuable gift. The mental injury that ended one career became the foundation for another—one built not on the promise of what might be, but on the hard-earned knowledge of what can go wrong, and how to fix it.

Kyle Koszuta continues to compete professionally while building That Pickleball School, an online education platform that has attracted over 1,000 members from more than 20 countries. His YouTube channel has produced nearly 90 educational videos, and his newsletter reaches thousands of subscribers weekly.

.svg)

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Suspendisse varius enim in eros elementum tristique. Duis cursus, mi quis viverra ornare, eros dolor interdum nulla, ut commodo diam libero vitae erat. Aenean faucibus nibh et justo cursus id rutrum lorem imperdiet. Nunc ut sem vitae risus tristique posuere.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Suspendisse varius enim in eros elementum tristique. Duis cursus, mi quis viverra ornare, eros dolor interdum nulla, ut commodo diam libero vitae erat. Aenean faucibus nibh et justo cursus id rutrum lorem imperdiet. Nunc ut sem vitae risus tristique posuere.