Who is Anna Bright?

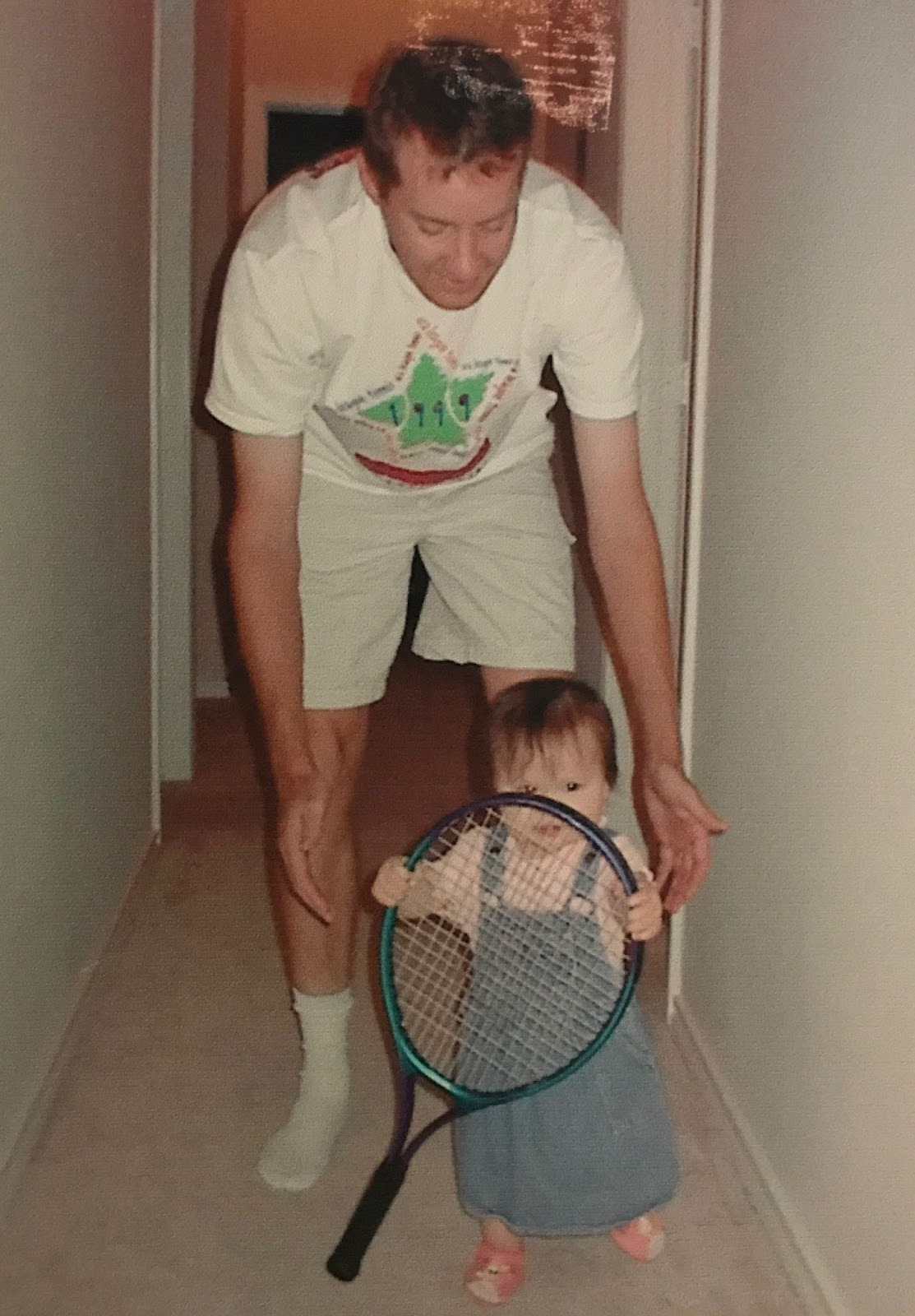

Anna Bright remembers the photograph: a toddler, perhaps two years old, gripping a bright orange tennis racket that was almost certainly themed around SpongeBob SquarePants.

Her father stands beside her, beaming with the satisfaction of a parent who has successfully transferred an obsession to the next generation. What the photograph doesn't capture, and what Bright wouldn't understand for years, is that the obsession would never quite take hold—at least, not in the way her father had intended.

"He was someone who was just really and truly obsessed with tennis," Bright tells me, her voice carrying the cool confidence of someone who has finally found her lane.

"Self-taught when he was like fifteen and walked on to a D1 team, which is really impressive for anyone familiar with tennis. And I think he was obsessed with tennis in the way that I became obsessed with pickleball. But I never really shared his true obsession with tennis."

This distinction—between inherited passion and discovered calling—forms the throughline of Anna’s story. At twenty-six, she has become one of the most recognizable faces in professional pickleball, a sport that didn't exist in any meaningful way during her childhood but now commands television contracts, celebrity endorsements, and breathless coverage once reserved for more established athletic pursuits.

Her journey to the top of pickleball, paradoxically, began with a childhood spent resisting the very activity that would eventually teach her what she was truly capable of.

Born with high expectations

The Bright family's devotion to tennis was primordial. When Anna was three or four years old, they moved to a house specifically chosen for its proximity to a tennis court across the street. Moving there was a statement of priorities, a family organizing itself around a singular vision of their daughter's future.

But the Bright household was also shaped by another kind of determination, one that crossed oceans and political upheaval. Anna's mother, Liping, had arrived in America with the resolve of someone who had witnessed history's darker moments firsthand. She scored the highest in her county on China's equivalent of the SAT—a feat that spoke to an intelligence that would later manifest in her daughter's own academic achievements.

"It was very tough to come to America for her," Anna explains. "Single woman, and she told them she didn't want to get married, she just wanted to get her education.”

The story has the compressed drama of immigration narratives: Liping dated Anna's father for six months, they married, and she became a citizen. What might seem like a calculated romance was, in Anna's telling, something more enduring.

Liping's influence on her eldest daughter would prove more complex. She had escaped a regime that crushed student protests and built a life in a country that rewarded individual achievement. That her daughter would eventually rebel against prescribed excellence, only to later choose her own version of it, carries a particular irony that would not be lost on either of them.

The young Anna who posed with that orange racquet was caught between these two forces: a father's tennis obsession and a mother's hard-won understanding that success in America required both fierce determination and strategic adaptability.

She was skilled at tennis—undeniably so—but skill without authentic desire creates its own form of resistance.

"My dad would be frustrated with me," Bright recalls. “He asked questions like why aren't you working on your swings in the mirror? Why aren't you watching this match?' And I'd respond, 'I don't want to. I don't care enough to do that.'"

The breaking point

At twelve, Anna Bright's body made a decision her mind had been struggling with for years. The stress fractures in her vertebrae—what she describes as "cracks from overplaying"—arrived as the result of a system pushed beyond its limits.

She had been training more intensively at the USTA facilities. The warning signs had been building: persistent back pain that the family initially dismissed as growing pains, the kind of minor discomfort that elite junior athletes are taught to push through.

In Arizona, where the previous year she had won a tournament in the twelve-and-under division, Anna was now seeded second in the fourteens. After a week of rest meant to address her back pain, she and her father flew west for what they expected would be a successful return to competition.

"I did my first practice in a while. It went okay, but then that night in the hotel, everything ceased and I was screaming in pain. I couldn't get out of bed." The memory still carries the shock of that moment when her body simply refused to cooperate. "I was close to being immobile, it was so bad."

The MRI revealed a fracture in her L4 vertebra—a young athlete's spine broken by the very activity that was supposed to be building her future. "It's pretty sad," she reflects now. "When you're not even thirteen and to be that hurt."

What followed was six months of absolutely no tennis, a period she describes as "probably the time in my life when I would most call myself a bit depressed." The enforced break created more than physical healing time; it opened a space for existential questions that had never been allowed before.

For a child whose identity had been entirely wrapped up in being "the tennis girl," the silence was both terrifying and revelatory.

The struggle extended beyond rehabilitation into academic life. During her recovery, attempting to continue her homeschooled education, Anna found herself failing in ways she'd never experienced. "I just felt like I was stupid," she admits, the vulnerability still evident years later. "I wasn't doing anything all day. I was just trying to do these classes and everything was hard…I didn't really get anything."

When she finally returned to tennis, the game had become foreign to her. "I was losing to people I'm not used to losing to. I wasn’t sharp and I wasn’t playing well."

The competitive fire that had once carried her to number one in the country in her age group felt more hollow now that her body’s own betrayal had made losing more of a possibility. What was she if not a winner?

The quest for normal

It was during this recovery period that Anna made the decision that would reshape her entire trajectory. "A few months after all of this, I went back into public school," she says. "I went back with only twelve weeks left of eighth grade. I told my parents that I wanted to go back now because I was still really under-socialized."

The decision to return to public school was a declaration of independence, a choice to prioritize becoming a complete person over becoming a tennis prodigy.

"I wanted to be a normal kid," she remembers. "I want to go to high school. I don't want to be homeschooled anymore. I want to have friends. I want to go to parties. I want to do normal teenage things."

The word "normal" carries extraordinary weight in her telling—not mediocrity, but the notion that a fourteen-year-old might be allowed to define her own version of success. Her parents, perhaps chastened by the severity of her injury and the depth of her unhappiness, listened.

But Anna Bright was not built for mediocrity, even when pursuing normalcy.

The same fierce competitiveness that had made her a nationally ranked junior tennis player found new expression in an unexpected arena: the classroom. "It was just very normal. And I really enjoyed it. And I really enjoyed the academics, actually."

The transformation was swift and telling. "I got four awards from my teachers. I proved I was smart. Which was a 180 from how I had thought of myself."

The academic convert

High school provided what middle school had promised: genuine social integration and the chance to excel at something she had freely chosen.

Her competitive instincts, denied their usual outlet on the tennis court, found perfect expression in the pursuit of academic excellence. The same qualities that had made her a formidable junior player—strategic thinking, the ability to perform under pressure, an obsessive determination to improve—now served her in Advanced Placement classes and standardized tests.

"I became valedictorian," she says, with the same assurance she brings to discussing her tennis accomplishments. But there's something different in her voice when she talks about this achievement—a note of genuine pride that had been absent when discussing her early tennis success.

Even more remarkably, she graduated a year early, adding another layer to an already impressive academic resume.

Her relationship with tennis during these years became something more complex. She continued to play—the skills were too ingrained, the court across the street too convenient to ignore entirely—but tennis had been relegated to something she did, not who she was.

The strain between father and daughter that had developed during her junior years gradually eased as tennis transformed from obligation into option.

The Berkeley years

College at UC Berkeley provided what adolescence had promised but only partially delivered: genuine independence and the chance to define herself entirely on her own terms. Bright earned a tennis scholarship, but by then the sport had been transformed from burden into opportunity—a means to an education rather than an end in itself.

Let’s not kid ourselves. No ordinary person can walk into the Berkley tennis program with the nonchalance Anna carries.

Success in collegiate tennis requires not just skill but the kind of mental toughness that comes from years of high-level competition. But even success felt different when it served purposes she had chosen for herself.

At Berkeley, Anna made another characteristically ambitious choice: she would double major in business administration and data science. The decision reflected both her competitive nature and her strategic thinking—she was positioning herself for a post-tennis life that would utilize her analytical abilities.

The academic rigor proved humbling in ways that tennis never had. "I decided I wanted to double major in data science and that was so humbling," she recalls. "I'm going to school in the Bay area and I'm in these computer science and stats classes and I realized that I'm just not on the level of some of these people."

The experience of intellectual struggle was simultaneously daunting and liberating. For someone who had always been naturally gifted at both tennis and academics, discovering the limits of her abilities felt like a form of honest self-assessment. "There are levels to this," she acknowledges, "and I don't think that you realize this until you've been in that environment. It can be shocking."

Tennis in college was both a continuation and conclusion. Bright played well, winning a Pac-12 Title with the Golden Bears and achieving a career high NCAA ranking of #13, completing the arc that had begun with that orange SpongeBob racquet. But graduation marked the end of tennis as an obligation and the beginning of tennis as mere background—a skill set waiting for its true purpose to be revealed.

Life on easy mode

During Anna's final year at Berkeley, about six months before graduation, she made a decision that would define her transition from college to career. She knew what came next: the corporate world was waiting, with its promise of structured success and financial security. But she also realized this might be her only window for something different.

"I decided I was doing the trail about 6 months before graduating," Anna explains. "Corporate life was always going to come after for me. I realized it was probably going to be the best window of time I would have to do something like that."

The Pacific Crest Trail—2,654 miles stretching from Mexico to Canada—represented a deliberate interruption in her carefully planned trajectory. Unlike her tennis career, which had provided structure and direction but never true passion, this would be something entirely her own choice.

"I felt like my whole life had been a little bit on easy mode to an extent because of tennis," she reflects. The full tennis scholarship, the guaranteed college admission, even the corporate job prospects that awaited her after graduation—all had felt predetermined rather than chosen.

"I wanted to do something to break the mold, to really challenge myself."

Rather than entering the working world immediately after graduation, Anna chose to spend her summer on the trail. It was a conscious decision to claim one last adventure before settling into the professional life she knew was inevitable.

The solo hike proved transformative in ways that tennis never had. Unlike the sport she had mastered but never loved, hiking demanded everything she had while asking for nothing in return except the satisfaction of completion. "I definitely did not love hiking as much as most people on the trail," she admits, "by the end of it, I was like get me off this trail! I was actually in a terrible mood on the last day."

Yet the achievement mattered precisely because it had been difficult and freely chosen—a final act of self-determination before entering the structured world of corporate America. The small tree tattoo on her thigh commemorates not just the completion of the trail, but the discovery that she could pursue and complete something purely for herself, on her own terms.

Then came pickleball

To someone who had spent decades perfecting tennis technique, pickleball might have seemed like a step backward, a dilution of skills she had spent years developing. The sport came to her through the most casual of invitations—her father, who had been playing recreationally, suggesting she might enjoy it and that she might even be better at it. After finishing the Pacific Crest Trail and before starting her corporate job, she had time to explore.

"I got home and I had a job that did not start until January, so I had two and a half months where I was just so addicted to pickleball," she recalls. "I had nothing else to do, so that was all I did."

The timing was fortuitous in ways she couldn't have planned. With months of unstructured time and the physical conditioning from her trail experience, Anna approached pickleball with the kind of focus she had once brought to academics. "Every single day I'd come home from playing at like 9 or 10 p.m. and I would just recap to my parents how it all went, how I was figuring things out."

The technical aspects of the transition from tennis to pickleball were less important than the psychological ones. In pickleball, Anna found herself doing all the things her father had once urged her to do with tennis: working on her technique voluntarily, studying matches with genuine interest, caring enough to pursue excellence for its own sake rather than to fulfill someone else's dream.

"The more I played, the more I realized how much strategy was involved," she explains, her voice taking on the animated quality that marks the difference between competence and passion. In pickleball, she discovered not just a sport she could play well, but one she wanted to play well, and that distinction has made all the difference.

The professional

Today, Anna operates at the intersection of athletics and entrepreneurship that characterizes modern professional sports. She maintains a newsletter for pickleball enthusiasts, navigates sponsorship deals with the savvy of someone who understands that athletic success in emerging sports requires business acumen, and speaks with the confidence of someone who has found her particular corner of the universe.

Her success has been rapid and comprehensive. Currently ranked number two in women's doubles and number three in mixed doubles, she has established herself as one of the premier players in a sport that barely existed when she was struggling through her tennis recovery.

Her medal count tells the story of sustained excellence: twenty-three golds, seventeen silvers, and twelve bronze medals in gender doubles alone, with 37 additional medals in mixed doubles and the occasional singles tournament.

She’s partnered with Anna Leigh Waters, the undisputed number one female player in the sport—a pairing that represents both a strategic career move and another example of Bright's willingness to make difficult choices in service of her goals. The partnership signals her continued evolution as a competitor who understands that authentic success sometimes requires uncomfortable decisions.

The same analytical abilities that served her in data science classes now help her dissect opponents' strategies and optimize her own game. But perhaps the most striking thing about Bright's current success is how it has integrated seemingly disparate aspects of her personality. The competitive drive that made her valedictorian, the strategic thinking developed through her business education, even the self-reliance learned on the Pacific Crest Trail—all find expression in her professional pickleball career.

The convert

The SpongeBob racquet of her toddler years has been replaced by the smaller pickleball paddle, but the fundamental question remains the same: What does it mean to be truly committed to something?

For Anna, the answer came not through external pressure, but through the recognition of her own authentic desires. She had always possessed an unusual degree of self-awareness—the same clarity that drove her to academic excellence, that made her strategic about using tennis for college, and that eventually led her to recognize when something wasn't quite right.

Whether pursuing valedictorian status or choosing the Pacific Crest Trail over immediate entry into corporate life, Anna has consistently demonstrated an ability to chart her own course, even when that course defied conventional expectations.

Her journey from reluctant tennis prodigy to passionate pickleball professional illuminates something essential about the nature of authentic achievement. Anna's success has never been accidental—she has always been driven, always strategic, always clear-eyed about her goals. What changed wasn't her ambition, but her willingness to apply that ambition to something she truly cared about.

Even her mother's journey from China to American citizenship provides a model for this kind of determined self-direction—the ability to see clearly what needs to be done and pursue it with unwavering focus. Perhaps Anna inherited that clarity of vision, that capacity for strategic thinking about her own life.

In the end, the most remarkable thing about Anna's story is not that she found her passion, but that she always trusted herself enough to keep looking for it. She could have settled for tennis success, could have accepted that excellence was enough regardless of fulfillment. Instead, she maintained faith in her own judgment, believing that somewhere there was something that would capture not just her ability but her genuine enthusiasm.

The convert's story is always more compelling than the true believer's, because conversion implies choice. Anna Bright chose pickleball the same way she once chose to walk from Mexico to Canada—deliberately, strategically, and entirely for herself.

That choice, rooted in self-knowledge and self-determination, has made all the difference.

.svg)

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Suspendisse varius enim in eros elementum tristique. Duis cursus, mi quis viverra ornare, eros dolor interdum nulla, ut commodo diam libero vitae erat. Aenean faucibus nibh et justo cursus id rutrum lorem imperdiet. Nunc ut sem vitae risus tristique posuere.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Suspendisse varius enim in eros elementum tristique. Duis cursus, mi quis viverra ornare, eros dolor interdum nulla, ut commodo diam libero vitae erat. Aenean faucibus nibh et justo cursus id rutrum lorem imperdiet. Nunc ut sem vitae risus tristique posuere.